To leave, or not to leave the EU, that is the question faced by many, ranging from individuals to businesses in the UK. The EU referendum, which is expected to take place on 23rd June, has triggered a wide range of discussions in recent months, with economic and political implications forming the basis of these debates. In this blog however, we focus on the economic case.

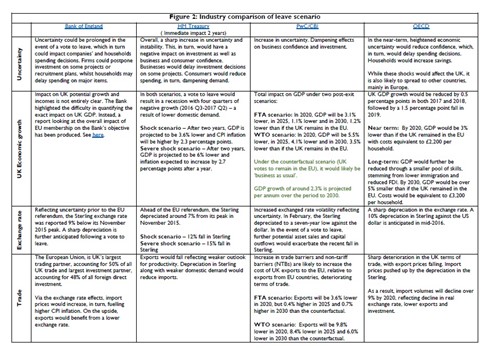

With so many reports churned out ahead of the EU referendum examining the economic effects of leaving the EU, all this information can be overwhelming for many. As a result, we have summarised the findings of key reports (Figure 2).

Although most reports go in great detail to show the economic effects of leaving the EU, they are merely assumptions and as result the margin of error is likely to be large. This doesn’t come as a surprise as it is generally difficult to quantify the effects of such an event, given the scale and complexity involved.

While most reports highlight uncertainty post-referendum, this is also the case in the run up. Indeed uncertainty ahead of the EU referendum is inevitable, but are we beginning to see this weigh on economic fundamentals?

Markit CIPS PMI for manufacturing, services, and construction reflected weakness in activity in April, with the former reporting a decline for the first time since March 2013. Business investment also declined 0.5% quarter-on-quarter in Q1, and was 0.4% lower compared to a year earlier largely reflecting firms delaying investment decisions until the outcome of the vote.

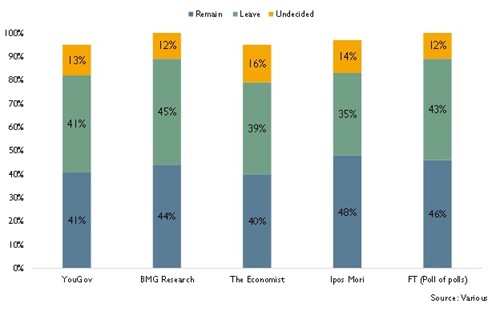

With less than a month to go and debates still ongoing, the polls continue to convey an uncertain picture. Figure 1 shows a comparison of the different polls, with remain and leave running neck and neck, exacerbating the uncertainty.

Figure 1: EU referendum poll tracker comparison (as of May 2016)

For a full list of individual polls see here.

A closer look at the breakdown shows that there is a generational divide. Those aged over 60 are in favour of a leave whilst those aged between 18 to 24 are in favour of remain.

Although the polls are a useful indication of voters intentions, there are a few things to be wary about. Firstly, the methodologies used by pollsters tend to vary from one another, with data collection methods (telephone, interent, etc) and weightings, the main differences. As a result, this is likely to skew results. Secondly, pollsters tend to alter their methodolgies with the recent case being YouGov for previously over-representing UKIP supporters. A similar situation was seen in the run up to the general election last year, where the polls overestimated the proportion of Labour voters and conversely underestimated the proportion of Conservative voters.

Despite these concerns, the polls, particularly the Financial Times poll of polls, have remained consistent in highlighting the uncertainty over the past few months. While this has been the main picture in the run up, the post-referendum period is unlikely to be any different. Whatever the outcome, economic fundamentals are bound to react in one way or the other. But in which direction and to what extent – remains unknown.