Speculation was rife in the weeks leading up to the publication of the government’s white paper on housing. Originally scheduled for release alongside the Autumn Statement in November 2016, were the constant delays indicative of a radical overhaul of its housing policy?

In the end, it was less bold than expected, which raises suspicions that there was some watering down. Instead, it reiterates current policy in place and provides an outline of proposals for future measures, many of which require deeper consultation (see this blog for a list of proposals). Whilst it lacked the detail some may have hoped for, however, it does provide a blueprint for how house building in England could be shaken up.

For local authorities: The white paper firmed up the government’s view that the role of local authorities in housing is one of land assembly. Councils will be expected to plan a five-year housing land supply and ensure that house building delivery is keeping track with local housing need. These local plans will be set in accordance with a new, standardised methodology – subject to consultation. Critics of current local housing needs calculations argue that councils setting their own methodology have incentives to minimise numbers to appease nimbyism. Finally, a proposed delivery test ensures that progress against these plans will be monitored, measuring net annual housing additions against local housing need. However, even at its full implementation at the end of 2020, local authorities can undershoot their plans by 35% before government intervention.

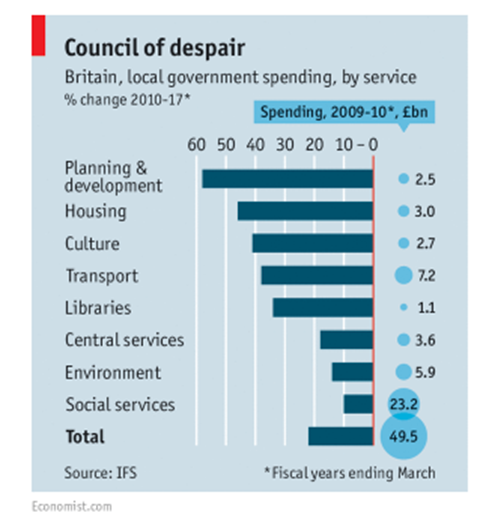

In return for the more rigorous planning approach, it is proposed that local authorities be given greater powers to issue completion notices and compulsory purchase orders on stalled sites, with the now-familiar ‘subject to consultation’ caveat attached. Financially, local authorities will be able to increase planning fees by 20% from July 2017 on the condition that the additional income is ringfenced for investment in their planning departments. This has consistently been a key ask from the house building industry since planning department budgets were one of the biggest casualties of the government’s post-recession austerity drive in 2010.

For large house builders: The white paper also conceded that another of developers’ bugbears may need to be reformed: developer contributions in the form of Section 106 agreements and the Community Infrastructure Levy. Often cited as the cause of long-winded negotiations that prevent a planning permission from becoming ‘implementable’ (i.e. getting on site), the government will announce at the Budget in Autumn how it plans to improve the speed, simplicity, certainty and transparency of the process. The other side of the bargain for the volume house builders is that government will consult on the requirement for them to publish their build out rates.

For SME and custom house builders: The number of SME builders has been on a long-term downward trend since 1988 and the white paper showed government is keen to start reversing this trend. Again, local authority land policies are emphasised, particularly for windfall sites (small sites not allocated in local plans that become available on an ad-hoc basis) and small undeveloped sites within existing settlements.

Build to Rent: The biggest signal that the government is moving away from its focus on home ownership came with its nod to the role of institutional investment, such as pension funds, in providing homes for private rental. Build to Rent hits the three main goals in the white paper. Clearly, it diversifies provision and it provides another tenure of housing that is not in competition with the major developers. It also has the potential to use modern methods of construction to increase build rates as the release of units is not sales-led. The investment yield is dependent on dwellings being completed quickly to bring in a constant flow of rental revenues. The first examples of Build to Rent in London demonstrate that high density flats around public transport connections also align with the government’s view of how housing sites should be prioritised.

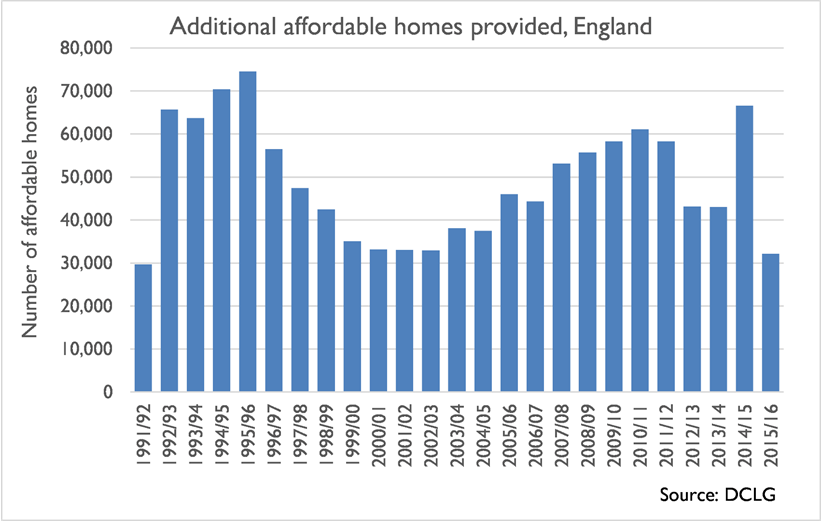

For housing associations: New measures for housing associations were thin on the ground. Of note, however, was the government’s recognition that housing associations need certainty over rent setting once the 1% annual cut regime comes to an end in 2020. Affordable housing delivery was the lowest in 25 years in 2015/16 as activity was disrupted by this and changes to the Affordable Homes Programme.

The best of the rest: Government also recognised that a long-term strategy for the housing market will need to broach the subject of a world without Help to Buy. Over its full period of operation since April 2013, the equity loan has accounted for 27% of private completions. It is due to end in 2020/21, but as yet, there is no plan for reining it in.

Some of the missing detail on Starter Homes was provided, however. There will be a household income cap of £80,000 (£90,000 in London) to match the shared ownership schemes, and to prevent speculative purchases, the 20% discount will be repayable for a period of 15 years and owners must be buying with a mortgage. Previously, there were plans for a mandatory requirement of 20% starter homes on all developments over a certain size, but this has been diluted to a 10% ‘expectation’. The Conservatives’ manifesto pledge for 200,000 homes of this type appears to also have been dropped.

The white paper is clearly not intended to be a quick fix and as Sajid Javid said, it will take time before all the proposals pass the consultation stage and develop into a solid policy. Nevertheless, if this is the government’s version of radical, let’s hope these measures don’t get watered down to something more moderate during the process.