How much does stamp duty raise?

Stamp duty, or Stamp Duty Land Tax (SDLT) to use its official name, is paid on the purchase of residential properties, the purchase of non-residential property such as shops, offices or agricultural land, and is also paid on new non-residential leases.

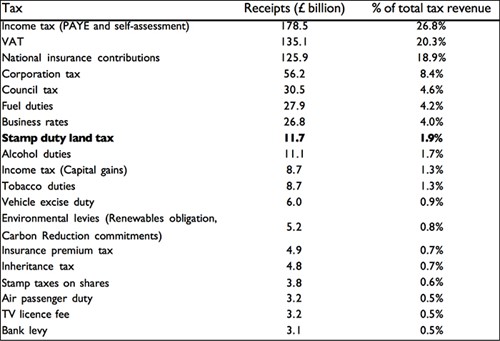

In total, stamp duty across these categories raised £11.7 billion for HM Treasury in 2016/17: £8.6 billion from residential property transactions and £3.2 billion from non-residential property transactions. It is the eighth largest tax revenue for the government and accounts for 1.9% of total tax receipts.

In recent weeks, residential stamp duty has hit the headlines, with calls to abolish, cut or reform it appearing in the press on an almost daily basis.

Recent changes

Stamp duty has already been tweaked frequently over the last ten years, from a stamp duty holiday that raised the starting threshold from £125,000 to £175,000 in 2008 and 2009, a stamp duty holiday for first-time buyers purchasing properties less than £250,000 between 2010 and 2012, the introduction of higher rates for properties over £1 million, £2 million or purchased through a company in 2011 and 2012, the switch from the 'slab' system to the income tax-like marginal 'slice' system in December 2014 and, most recently, the 3% surcharge for buy-to-let and additional properties since April 2016.

Since its introduction in December 2003, stamp duty has been modified 12 times. Can any further changes be made?

Abolish

The 'Call Off Duty' and 'Stamp out stamp duty' campaigns by Property Week and the Taxpayers' Alliance respectively, put forward the argument that a tax on transactions makes purchasing a property less appealing for first-time buyers with stretched budgets and discourages transactions further along the chain.

However, given that residential stamp duty raised a record £8.6 billion for HM Treasury in the last financial year, even at a time when property transactions volumes have remained muted, the fiscal argument to keep stamp duty in place is unbeatable. Furthermore, a homebuyer sets their purchasing budget as a function of house price, stamp duty and legal and removals fees. A fall in the amount of stamp duty payable will be reallocated to the house price component. This capitalisation into higher house prices would represent a windfall gain for house sellers, with HM Treasury losing out.

Seller pays stamp duty

A policy suggested by Yorkshire Building Society centres on removing the stamp duty burden for first-time buyers and lowering it for those moving up the housing ladder by shifting liability to the seller. For government, its tax revenues are unlikely to be changed given stamp duty is still being paid on each property bought and sold.

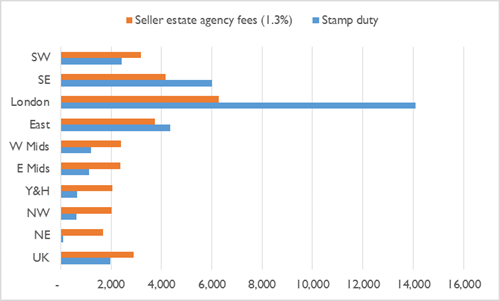

However, sellers will now be facing stamp duty and estate agent fees, which may discourage transactions. Based on the average UK house price and average estate agent commission of 1.3%, sellers will face a cost of £4,859 to sell their property, rising to £20,366 based on an average house price in London. If not discouraged from selling in the first place, these higher costs are likely to be factored in to asking prices, which will either be met and lead to rising house prices, or buyers' offers reduced and refused, stalling activity.

Furthermore, with the highest stamp duty bills payable by downsizers and those at the top of the chain, these sellers may be further deterred and stall the supply of higher-value or end-of-chain properties coming on to the market.

Stamp duty cut

Changing from a 'slab' to a 'slice' system in December 2014 reduced the stamp duty bill for house purchases below £937,500, equating to all except 2% of properties. In 2015/16, the financial year after the change, sales of properties over £1 million totalled 19,100. This was the highest since HMRC records began in 2005/06, yet still only 1.6% of total transactions. By contrast, this market segment raised £2.6 billion in stamp duty revenues, or 36.0% of the total.

Those involved with the higher-value end of the market have been more vocal in calling for a reversal in the subsequent amendment to stamp duty: the 3% surcharge for additional properties that adds £45,000 to the cost of purchasing a £1.5 million property. Transactions volumes over £1 million dropped 9.9% in 2016/17 and volumes over £2 million fell 14.6%. For transactions in the £1-2 million price band, 27.0% were subject to the 3% surcharge and 40.0% in the over £2 million band. It is difficult to solely attribute the fall in transactions to the higher stamp duty, given that June 2016 saw the EU referendum and greater risk aversion and uncertainty, coupled with an oversupply in super-prime residential in central London resulting in falling prices and deteriorating confidence.

Nevertheless, since the introduction of the surcharge, which has also been paid on 29.0% of properties under £250,000, buy-to-let lending has been falling and the late amendment to levy it on Build to Rent properties was also badly received. In 2016/17, the 3% element raised £1.7 billion alone (19.3% of all receipts that year) and given that it appears to be having the government's desired effect of reducing buy-to-let demand and raising revenue, it is unlikely to be cut unless the drop-off in demand from this segment of the market begins to spread to the wider housing market and impact on house building and Build to Rent activity.

Stamp duty holiday

The last stamp duty holiday ran between March 2010 and March 2012, under which first-time buyers paid no stamp duty on purchases under £250,000. Among others, Labour pledged another stamp duty exemption for first-time buyers in its election campaigns for 2015 and 2017. HMRC's own assessment of the last holiday was not a ringing endorsement for the policy, however. It found that first-time buyer transactions were only 0-2% higher than they would have been in the absence of any relief. It also found evidence that, again, the tax saving was capitalised into a 0.5-0.7% increase in prices.

Stamp duty dependent on EPC rating

Since funding for the Green Deal was cancelled in 2015, a variable rate of stamp duty has been suggested as a replacement incentive for energy-efficient home improvements. The idea is that homes with an EPC rating above a C or a D receive an incremental stamp duty discount for each band above this threshold when next purchased. Homes with an EPC rating below this threshold are subject to a stamp duty penalty mirrored down the EPC rating scale. This aims to incentivise buyers to purchase energy-efficient homes, and for homeowners to make their homes more appealing, as any stamp duty savings for the buyer are likely to be factored in to values. The main drawbacks centre around lower-value properties, where the potential stamp duty differentials between an EPC A-rated property and an F-rated property are hundreds, rather than thousands of pounds. Furthermore, there are 33 local authority areas where the average house price is less than the £125,000 starting threshold for stamp duty and, therefore, would not receive any tax relief. Even for higher-value homes, costly measures such as external wall insulation, at a cost of £8,000 to £22,000 according to the Energy Saving Trust, may still outweigh any stamp duty discounts.

Conclusion

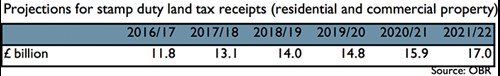

Whilst the pressure for stamp duty giveaways in next month's Budget grows from estate agents, first-time buyers and factions of government itself, the prevailing financial conditions and the Chancellor's conservative fiscal stance imply that any change is unlikely. The weaker productivity growth expected in the next set of forecasts from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), the government's rising costs of servicing debt on inflation-linked gilts and the prospect of a housing market slowdown radiating beyond prime central London, mean that such a stream of tax revenue will be too important to cut. The consecutive annual rises in receipts projected in the OBR's current forecast perhaps illustrate the strongest argument to stay put.