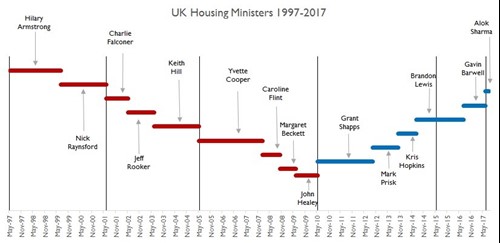

The appointment of Alok Sharma as Minister for Housing in Teresa May’s new government back in June marks the 15th holder of the position in 20 years. In a sector that is visibly high on the political agenda, then clearly the high turnover of ministers – serving an average term of just 16 months – begs the question of whether this provides a stable political backdrop to see policy proposals through to fruition and achieve the government’s much-publicised goals for increased housing delivery.

However, ministerial positions with a higher churn rate than the manager of the England football team (11 since 1997) are not uncommon. The portfolio covering construction has changed hands 14 times, there have been 15 Chief Secretaries to the Treasury and the similarly political hot potato of immigration has been taken on by 12 ministers in the last 20 years.

The frequency of Cabinet reshuffles outside of general elections is perhaps the wider problem. Take the particularly busy period for housing ministers between 2008 and 2010. Peter Hain’s resignation from the Department for Work and Pensions over allegations of funding irregularities in January 2008 saw the end of Yvette Cooper’s (relatively) long 32-month tenure as housing minister as she was moved to the Treasury, to be replaced by Caroline Flint. Then, six months into Gordon Brown’s premiership came his first reshuffle: Caroline Flint, who had spoken out against the leadership, was ‘demoted’ to Minister for Europe and Margaret Beckett was brought back into government in the housing role. Nine months later, she and four other Cabinet ministers resigned, again marking discontent over the Brown leadership. Replacement John Healey’s run from June 2009 was then scuppered by a Conservative win at the 2010 general election.

It does, therefore, appear as though internal politics within government is the main reason behind high turnover of those in ministerial positions. Construction, and housing in particular, are highly cyclical sectors that, in the absence of economic certainty, would at least benefit from stability at a policy making level. Immediate issues after the Grenfell Tower fire also emphasise how the passing of the portfolio means promised reviews and policies can easily get mothballed or sidelined, instead of providing the continuity required for the brief. Can Alok Sharma provide this stability and continuity? Well, that’s at the whim of the next reshuffle: impress and he’ll get a promotion, struggle and we’ll be welcoming minister number 16.