Last week saw the publication of Labour’s Green Paper on social housing. Like all good housing announcements, it came with a big number target – 1 million “genuinely affordable” homes over ten years. And like recent housing papers from the incumbent government, it wasn’t short on proposals to shake-up delivery.

- The affordable rent tenure, which allows rents of up to 80% of market rents will end. It will be replaced by a social rent tenure, which will form the majority of social housing provision. Rents will be set using the current formula that is based on local incomes, property values and the size of the property. Living rent homes will be introduced, with rents set at no more than one-third of average local household incomes, as well as low-cost home ownership homes through a FirstBuy scheme, which will be for discounted sale, with prices set so that mortgage payments are no more than one-third of average local household incomes. Linking rents to local household incomes seems more sensible than the current system that uses market values, as the latter can be pushed higher by ‘premium’ new build units, especially in town and city centres, regeneration areas and around transport hubs. However, with FirstBuy it is not clear how higher interest rates (a distinct possibility over the timescale we’re looking at) will impact on calculations.

- A presumption in favour of affordable housing to be included on ALL housing development including, notably, sites of fewer than 10 units and permitted development such as offices to residential that accounts for a rising proportion of net housing supply.

- A suspension of Right to Buy

- Local authorities able to purchase land for local plans at existing use values and ending the ‘fire sale’ of public land to the highest bidder

- Encourage the use of offsite/modern methods of construction for affordable housing

- Making provision of apprenticeships a condition of grant funding

- A focus on design, quality and fire safety, including sprinklers for all high-rise residential buildings

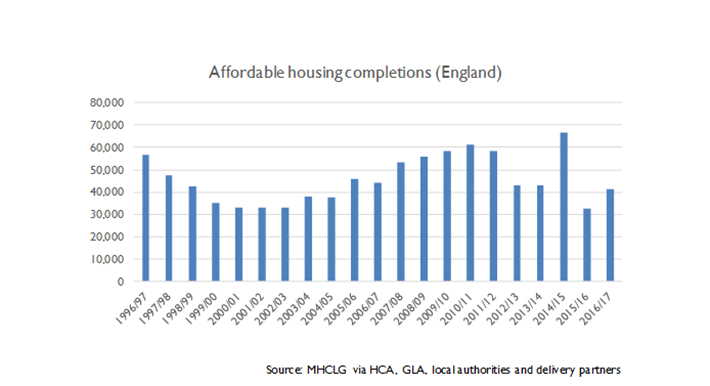

Taking the headline figure of 1 million affordable homes over ten years – 100,000 per year – how does this compare to current delivery?

Affordable housing completions in 2016/17 were 41,530 and the highest annual figure in the last 20 years was 66,700. So, considerable uplift is required.

Encouragingly, the Paper proposes establishing an Office for Housing Delivery to monitor and audit housing delivery against the 1 million target, a measure that aims to make such pledges more believable. David Cameron’s 200,000 Starter Homes from 2015 are a mythical case in point.

And the funding?

The plan is to raise grant investment to £4 billion a year, which will have to be squared with other departments competing for funding, and the NHS presumably high up on the Labour wishlist.

The Paper also proposes measures to reduce land costs for affordable housing sites, including an English Sovereign Land Trust to buy land with local authorities at existing use values (rather than significantly higher values post-planning permission) and ending the ‘fire sale’ of public land to the highest bidder. Currently high land costs and bidding wars mean that other elements of the house builder viability equation have to be tweaked to maximise the price that can be paid for the land purchase: the gross development value, affordable housing provision or contributions, development costs and profit. Costs and affordable housing are typically the first to be pared down. By reducing the land cost element to existing use values, it aims to limit the possibility of bidding wars and increase affordable housing contributions. However, the counter-argument is that landowners may sit on their hands in anticipation that the next government in five years’ time will return to the system of higher land values determined by planning approvals for future use.

The policy proposal that is likely to get the most plaudits is the raising of local authority borrowing caps to prudential limits – i.e. affordable and sustainable levels. Local authorities in England built only 1,730 homes in 2017 and the 20-year average is just 723. The Local Government Association, among others, has been calling for greater freedoms over borrowing for housing investment for a long time, to raise the contribution from council house building closer towards the 27,410 built by housing associations last year. Local authority planning and development budgets have been slashed since 2010, however, and bringing these roles and skills back in-house is going to take time.

Some solutions are offered for the usual skills question of who will build the promised increases in housing volumes. Labour proposes that apprenticeships will be a condition of grant funding, although this could lead to similar issues experienced with labour clauses in Section 106 agreements, in that the focus is on apprenticeship starts for each project, with training then stalled as building completes and new developments require a new intake of apprentices. A nod is, of course, given to offsite and modern methods of construction, that lend themselves more to the proposed tenures of housing that can be built quicker than the absorption rates of market sale. For the CPA, the proposal for increased funding where local materials are used is an interesting one, but clearly throws up questions about the understanding of our industry.

In conclusion, the Green Paper offers some proposals that plaster over the weaknesses in current housing policy, namely on publicly funded housing construction and plans for a return of local authority house building. There are naturally some issues, but let’s not forget that the biggest barrier of all for Corbyn, Healey et al is being first past the post at the next election in 2022.